"The Revelation of Jesus Christ, Made Known to John" (Continued)

The Apportioning of Mankind (Rev. 20:4-15)

To this point, John has been very careful and thorough regarding every event he has described; indeed, there may not be one he has not repeated a number of times in the effort to give us fuller insight and elucidation. But now--at least until he gets to the new Jerusalem (which is only one chapter away)--he rushes along at such a pace that seemingly very important matters get glossed over and serious questions are raised which he shows no interest in answering. Part of his reason may be that he sees these as events that are not particularly pertinent to the present lives and decisions of his readers. The maintaining of faithfulness through the end-time and the decision as to which supper we want to attend at the parousia--yes, these very much involve us; but with the parousia, our decisions have been made and matters are out of our hands, so to speak. Nothing is to be gained by curiosity and argument concerning this post-parousia period. Consequently, John treats it rather casually and encourages us to do the same.

Nevertheless his major purpose and intent in this chapter seems quite evident; and it is important. In parallel scenes of the millennium and the final sentencing, he wants to portray the postparousia fate of the Lamb's people on the one hand and the beast's people on the other. None but the Lamb's people appear in the millennial scene; none but beast's people in the sentencing scene. John's interest is focused entirely upon the destiny of these two groups; it is only toward matters of physical and chronological detail that he is casual. He is no more interested in doing a photographic study here than he was earlier. So recall Picasso's Guernica and consider that a painting can communicate great truth even when the literal details are quite discrepant--indeed, can focus upon a deeper level of truth by deliberately making the details discrepant. The very presence of discrepancy is a signal to quit fussing with details and look to the central truth involved.

Rev. 20:4-10, Life: The Millennial Resurrection

4 Then I saw thrones, and those seated on them were given authority to judge. I also saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for their testimony to Jesus and for the word of God. They had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. 5 (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended.) This is the first resurrection. 6 Blessed and holy are those who share In the first resurrection. Over these the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him a thousand years.

7 When the thousand years are ended, Satan will be released from his prison 8 and will come out to deceive the nations at the four corners of the earth, Gog and Magog, in order to gather them for battle; they are as numerous as the sands of the sea. 9 They marched up over the breadth of the earth and surrounded the camp of the saints and the beloved city. And fire came down from heaven and consumed them. 10 And the devil who had deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and sulfur, where the beast and the false prophet were, and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.

That John spent about twice as many chapters describing the three and a half years of the end-time as he does verses describing the thousand years of the millennium indicates the order of speed-up that has occurred.

Because we now are to focus upon the fate of "mankind," it would be helpful to review how John has handled the matter thus far. He consistently has seen humanity as divided into two--and only two--major categories: all men are marked as belonging either to arnion or to therion; there is no third alternative. But further, John has shown no real interest in establishing distinctions within either of the groups; he is content to speak simply in terms of the groups as such. Thus, for instance, he has told us nothing about the beast's people who have died, where they are or what their situation might be; bad people, living or dead, he has treated simply as a unit.

And thus, for another and more critical instance, although John began by recognizing the distinction between the church of the living (on earth) and the church of those who have died (in heaven), he proceeded to rather wipe out the line between them--but without making it completely clear as to just how this takes place. Now, in this millennial scene, he has lost the distinction entirely; and that creates a real problem in logistics--if one insists on reading John photographically.

The account clearly intends to deal with the Lamb's people en masse. The scene obviously takes place on earth-and yet everyone in it seems to have come from heaven, for they are those who have died, and everybody in sight gets resurrected. "But certainly there will be living Christians on earth at the time of the parousia; where do they come in? Can a person be resurrected if he hasn't even died yet?" Questions, questions, no end of questions! And I rather think John would answer them by saying, "Oh, please don't hang up on trifles! God can and will talk care of details like that; and there is no reason why you need to know how he will do it. No, please hear what I am trying to say, that the Lamb's people will all be graduated into second-order LIFE!"

While we are looking at problems, let's consider the other big one; it arises out of Rev. 20:7-10. The scene, with its reference to "the hosts of Gog and Magog," is based directly upon Ezek. 38-39; there is no mystery in that respect. But recall the situation at this point: "Babylon"--all the power and seduction of worldliness--is gone and completely out of the picture. Both Antichrist and the Unholy Spirit, with all their deceitful wiles, are also lost and gone forever; and the Dragon himself has been off the scene for a thousand years. The parousia account implied that the vultures had eaten all the human supporters of the Evil Trinity. It is hard to conceive what representatives of Evil might have been around during the millennium and how they could have maintained themselves; and indeed, the text of the millennial scene gives no hint of their presence.

But then, what power can Satan possibly control for this untimely effort of verses 7-10? Where do these supporters come from the hosts of Gog and Magog? Has Satan any chance at all of seducing these saints who already "have passed through the great ordeal and washed their robes white in the blood of the Lamb," who already have won the victory which, we have been told, makes them immune to the second death? Does John here mean to reopen the door he spent nineteen chapters getting closed? Is he undoing what Jesus has done and putting the fate of the world back into doubt? Is he implying that, even with his death-and-resurrection and parousia, Jesus has not yet done enough entirely to eliminate the threat of Evil?

Although a literal reading of this passage would make such implications as much as inevitable, I am confident that they are not at all what John intends. For one thing, if he had seen this as a serious--and even critical--juncture in his story, he would know that it requires much more than four short verses to deal with it--Four verses in which to describe a new and sudden outburst of Evil that overcomes its defeat in the parousia to mount a new threat to the world, seducing the saints, and even laying siege to the church (Jerusalem, "the city that God loves") before God can find the wherewithal for winning a victory that must be counted even greater than Jesus' parousia? No, that John can do it in four verses indicates that he must have something much less crucial and decisive in mind.

To me, the evidence suggests, rather, that this last stand of Satan is used as a somewhat arbitrary symbol for marking the conclusion of the millennium. What demarcates the millennium from the events preceding and following it? Well, it begins with Satan being taken prisoner at the parousia and ends with his being dumped into the lake of fire. (It is noteworthy that John does not see Satan's final fling to be significant enough even to call for the presence of Jesus in the scene.) So let this incident play its role as a boundary marker of the millennium. But when we try to go beyond that, I think John would say, "You're trying to make it say much more than I ever intended it should."

"But," the next question comes, "why do we need this millennium at all? It has created nothing but problems. Wouldn't both the plot line and the theology go much more smoothly if John were to move from the parousia directly to the new Jerusalem--or at least to the final sentencing?"

In one sense, John almost does this. He does not move directly from the parousia to the new Jerusalem; but he does move quickly (one brief chapter). We need to keep this proportioning in mind.

Even though a time period of a thousand years intervenes, John clearly wants to establish that the coming of the new Jerusalem is a direct consequence of Jesus' parousia--this is the essential sequence. Yet we will see that John could not have included the final sentencing without including the millennial scene as well; the resurrection of the saints is necessary to establish that they are not involved in the sentencing. But even to omit the two scenes together would destroy the structure of John's theology; he needs to establish the situations of both the Lamb's and the beast's people before his new Jerusalem scene can say what he wants it to.

In the present millennial scene, it would seem that John is more interested in the "resurrection" aspect than in the "thousand years" aspect; but let us begin with the thousand years and then move to the resurrection. I see two primary reasons why this thousand-year period is a "must" in John's thought. Look at the Time Line diagram. The symmetrical counterpoint of John's approach is very important to him--and not simply for aesthetic reasons; it is a means by which he affirms the justice and glory of God. The beast and his people got a three-and-a-half-year period on earth when they pretty much had things their own way, while the Lamb and his people had to take it in the neck (the Lamb in his crucifixion, his people in their faithful martyr-witnesses). Yet, even with the Lamb's eventual victory, that period cannot be allowed to stand unanswered; history would not have come out "right," full justice would not have been done, and "the very truth of things" would not have been manifested. The Lamb and his people deserve a thousand years (a large: full, complete number as over against the broken "3 1/2") of reign on earth--to put that end-time nightmare into proper perspective, if for no other reason. Our tendency (living in the time we do) is to think of history as constituted solely of nightmare. Not so, says John, this world-history of ours belongs to God; and, for every three-and-a-half-year nightmare, it includes a thousand-year reign with Christ.

But the millennium also serves another purpose for John. As we have observed, he does not make many distinctions between person and person within the total body of the Lamb's people; for instance, he doesn't particularly care whether you are a living Christian or one who has died. Yet there is one distinction that is important to him--and he has indicated so previously.

Some Christians were called upon to make a faithful witness of an order that involved actually laying down their lives for the sake of Christ and the brethren; these are the martyrs, in the strict sense of that term. Many more Christians, although faithful to their own call, won their crowns without having to make this greatest act of commitment. The distinction is not an ultimate one, John knows; both types of Christians finally come out indistinguishable. Nevertheless, he feels that the martyr-saints do deserve some special recognition and honor, and the millennium affords an opportunity for this.

Verses 4-5, unfortunately, are not crystal clear; but we will do the best we can with them. First, in identifying the martyrs, John does call them the "beheaded"; but he probably means this in the general sense of "executed" rather than specifying for honor only those who met death in the one particular way. The original Greek does have an "and" preceding the phrase "They had not worshipped the beast..." If we insert it and understand the sentence as identifying two groups rather than one, the entire passage will render better sense.

- The first group, then, consists of those Christians who lost their lives for the sake of God's word and their martyria Jesu.

- The second group consists of the rest of the Christians, who had not worshipped the beast or worn his image but who had not been martyred, either.

Apparently John means to say that the first group comes to life at the beginning of the millennium. "Coming to life," or "resurrection," means, now, graduating into second-order LIFE, the quality of life that will characterize the new Jerusalem, the ultimate of human experience that, we are told, is forever immune to anything of death. John never uses these terms in any other way. "The rest of the dead," who come to life after the thousand years are over, surely must intend the second group of Christians; the dead among the beast's people certainly are not eligible for "resurrection" (the next scene will find them still very much "dead"), and they are not even in John's picture at this point. But with the raising of the second group, any distinction between the two is lost; their history proceeds as that of the one church. The martyrs' recognition was that of receiving their prizes a little ahead of the others; their final status is in no way different.

In fact, perhaps as a means of emphasizing that no ultimate distinction is involved, John apparently groups both raisings together as constituting "the first resurrection." The millennial experience is that of one resurrection in two stages--and all Christians are included in either one stage or the other. There is nothing to indicate nor any way of conceiving that any of God's people has been left out. The church as a whole has graduated into LIFE. At this juncture, then, the distinction between the Lamb's people and the beast's is easy and obvious: the Lamb's people are all in second-order LIFE, the beast's all in first-order death.

John here chooses a very intriguing phrase; let's give it careful notice. He calls this scene "the first resurrection." That word "first" carries with it some implications--just as surely as if I were to refer to "my first wife." There is no sense in referring to an item as "first" unless it is one of a series, unless there is at least a "second" to follow. It is true that John nowhere speaks of a "second resurrection"; however, there is a spot where there is room for it and where John may be hinting that it takes place. Of course, we are not yet in position to make any decision in this regard; but do keep in mind that explicitly (in two different sentences) John has called this millennial experience "the first resurrection."

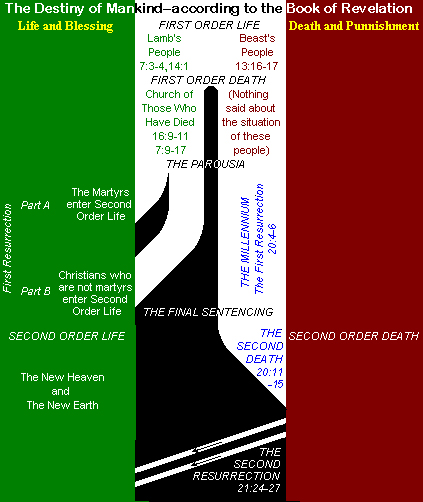

We present here a chart designed to give graphic representation to what we have been saying--and what we have yet to say. Let us examine the appropriate portion of it now.

The chart portrays the destinies only of "mankind"; to have tried to include those of the various supernatural personages would have made it too complicated. It is a flow chart that moves downward through history. A turn to the left marks a move toward Life and Blessing; a turn to the right, a move toward Death and Punishment.

At the top, all men begin together in first-order life. It is here that their fates first are decided, and the division takes place as they accept the seal either of the Lamb or of the beast. However, in first-order life, those seals are invisible and the two groups inextricably mixed.

A real complication in the charting is that all men do not experience first-order death at the same time; some are already in first-order death while others are still in first-order life--and this is true of both the Lamb's people and the beast's. John handles this complication mainly by ignoring it; and the chart does the same. Surely there is some kind of separation between the two groups at death; but John makes little of it. He has shown us, in heaven, the saints who have died; but he has mentioned not a word about the beast's people who have died. The important thing to note is that John does not agree at all with the idea that most people seem to hold on the subject. He does not make the moment of first-order death a critical juncture. The Lamb's people do not, at that point, automatically jump into the finale of second-order LIFE; consequently, John's pictures of the saints in heaven still carry elements of incompleteness and more yet to come. Likewise, the beast's people do not, at that point, automatically proceed into second-order DEATH and the lake of fire. John does not show us individuals going, at individual times, to individual destinies; he has us waiting for one another and then proceeding as groups. (And by the way, the rest of the New Testament agrees with John on this point.)

With the dead of both groups being in a "holding pattern," it is the parousia of Christ that truly puts things into motion for the first time. With that parousia comes "the first resurrection," graduating the Lamb's people clear over to the left-hand side of the chart and into second-order LIFE. That resurrection takes place in two stages, including first the martyrs and later the rest of the Christians. The two stages together span the millennium.

With the saints safely "home," we turn our attention now to the beast's people, who have been waiting patiently all this time in "hold."

Rev. 20:11-15, Death: The Final Sentencing to the Lake of Fire

11 Then I saw a great white throne and the one who sat on it; the earth and the heaven fled from his presence, and no place was found for them. 12 And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Also another book was opened, the book of life. And the dead were judged according to their works, as recorded in the books. 13 And the sea gave up the dead that were in it, Death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and all were judged according to what they had done. 14 Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire; 15 and anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire.

In the previous scene, the Lamb's people went to their destiny; now, in its counterpart, the beast's people go to theirs. This scene usually is referred to as "The Last Judgment"; I have changed that wording for a very particular reason. A "judgment" usually is thought of as a situation in which the guilt or innocence of the defendants has not yet been determined, in which the meeting takes place for that very purpose, in which there is just as much opportunity for the defendants to be found innocent as guilty.

But none of that is the case here, and I have changed the wording to reflect the fact. That these people are here and are dead is proof enough that they belong to the beast and thus are guilty. Plainly, none of the Lamb's people is anywhere around; none of them is dead, having all graduated into second-order LIFE and by that act been guaranteed that "over these the second death has no power." No, even before anything like "judgment" takes place, it is evident that everyone present is guilty; they are gathered here only for the handing down of sentence.

The scene transpires before "a great white throne," but John does not specify whether it is God or Christ upon it--probably not Christ, because John has shown some tendency to keep him out of such scenes. Notice that the defendants consistently are described as being "dead"; they do not need to be resurrected or brought back to life in order to act their roles; and John would not be willing to use such terms in their connection. The record books are produced not on the chance that some of them might be found innocent but simply to prove to them that their sentences are just. Their very desire to justify themselves "upon the record of their deeds" is a mark against them; and of course, their deeds will show them to have been minions of the beast. Obviously, their names will not appear in "the roll of the living"; if their names were there, these people wouldn't be here, they even now would be "living"--living the second-order LIFE of the saints.

All of the dead--which is to say, all the beast's people--are involved. The sea, that garbage can from which the beast originally came, gives up its dead; Death and Hades give up all they have been holding. "Death and Hades," that ghastly pair for whom, at the very outset, Jesus told us he was holding the keys and who rode across the earth on the pale horse--they get tossed into the lake of fire. With this jettisoning of Death and Hades, every one of the supernatural representatives of Evil has disappeared for good. Things can't be anything but very, very different from now on.

But the beast's people, too, now go into the lake of fire; what does it represent in their case? Well, don't jump to the conclusion that it necessarily means the same thing for them as for the "supernaturals"; there is a difference! The "supernaturals" are symbols of pure (if that's the right word) evil. The "people," although gone bad, are nevertheless persons who were created in the image of God, whom "God so loved," who are "brothers for whom Christ died."

Recall, however, that to this point John has not described any special punishment for them. Yes. they had to endure the end-time traumas--but so did the Christians! Yes, they have suffered first-order death-hut so have the Christians! Yes, some of their deaths were quite gruesome (being eaten by vultures)--but so were the deaths of some of the martyrs! But now John wants to say (taking a word from Paul): "The wages of sin is death!" Mere first-order death will not fill the bill in that statement; saints die first-order deaths just as sinners do. But no, to reject the Lamb is to reject LIFE; and outside of LIFE there is only DEATH. Through sin, natural death leads on to death to the second power; the person kills himself spiritually, becomes not merely a dead person but a supporter and promoter of DEATH. John, here, is not speaking in terms of any exaggerated retribution, vindictiveness, or cruelty; he does not use the sort of language that earlier was directed against the "supernaturals." He simply is stating a law of the universe: to reject the way to LIFE is to take the way of death; and the way of death can lead nowhere but to DEATH.

|

Copyright (c) 1974 |