Study One: The Beloved Disciple's Name and Story

Opening the Case

The Problem

Before we can even begin to treat the Fourth Gospel (let alone the identity of the Beloved Disciple), we need to get a good bit of practice in handling simply the raw data that could come from any of the Gospels. Thus, a major hope for this study is that it might give the laity who have had but slight contact with biblical scholarship at least something of a feel for what Bible scholars are supposed to be about and how they do what they are supposed to be about. To the laity, this is probably a more unfathomable mystery than the identity of the Beloved Disciple. They honestly can't figure what Bible scholars could possibly be good for, and they must think that scholars pursuing their work are like psychics--super-intellectuated beings who read a passage of Scripture, close their eyes, "ponder" for an interval of minutes, hours, or days, and then open their eyes to declaim the very TRUTH OF GOD (in incomprehensible terms having no apparent connection with the Scripture just read). Now I admit I have seen studies that seem to have been done that very way, but such is not true scholarship. Our case will demonstrate only one of the many methods scholars use, yet readers will find themselves (subconsciously, I hope) actually being scholars rather than just hearing reports from or rumors about them.

Further, I hope that readers (again, subconsciously) will come to sense the fundamental nature of the Gospel evidences with which we are dealing. By "Gospel evidences" I have in mind the historical data, the "factual knowledge bits" that come from any and all of the four Gospels in the form of names of individuals or places involved in the story; chronological hints about what happened before or after something else did; and accounts of what happened where, who did what, and who said what. The problem is that "people" on the one hand and "scholars" on the other are of two different minds regarding what those "factual knowledge bits" actually represent and how they properly are to be used.

"People" tend to assume that the collected "bits" from all four Gospels are jigsaw pieces that can be fitted together to form one complete and uniform puzzle picture. Once we get them properly arranged and related, these pieces will give us the one real, true, historically factual picture of Jesus and his career--an accurate biography of, Jesus, if you will.

The difficulty is that the "scholars" (the professional puzzle-doers) cannot for the life of them use all the pieces and make them into the uniform puzzle picture that is supposed to result. Yes, many individual puzzle-doers claim to have the solution. The trouble is that no two of them come up with the same picture; each tends to produce the portrait of Jesus he had in mind before even starting work on the puzzle. It is apparent that these people subconsciously are selecting their pieces to compose a picture rather than discovering the one the puzzle supposedly embodies.

Scholars now generally agree that one root of the problem is the assumption that the one uniform puzzle picture can be produced without giving attention to the color of the back of the various pieces--that is, without paying attention to the source of any piece, whether it was originally a piece of Mark, of Matthew, of Luke, or of John. To mix together the pieces of four different puzzles and then to try to arrange them to form one picture probably was not the smartest way to go at jigsaw puzzling. Scholars have found that we will get farther by using "Mark pieces" to build a "Mark picture," "Matthew pieces to build a "Matthew picture," and so forth--if we then can live with the fact that each of the Gospels presents a unique picture that will never completely jibe with the others.

Scholars also realize that, when anyone claims to have arranged all of the pieces to give us one complete puzzle picture, he inevitably has done (subconsciously, we assume) a certain amount of "fudging" (let's not call it "cheating"). I propose that happens in three ways:

- When confronted with some obstinate pieces that just cannot be made to fit anywhere, we tend to brush them surreptitiously off the table into the wastebasket--to conveniently look the existence of biblical evidence that disagrees with the evidence we have chosen to use at a given place.

- With other pieces we simply snip off the "peninsulas" (or whatever those parts that stick out are called) that keep them from fitting where we think they belong. Again, we do a mental trimming and conveniently dispose of any details that don't quite fit the picture.

- Conversely, we resort to using Silly Putty to add a needed peninsula to a piece that's too small, reshaping it until it will fit the hole we have in mind for it. This Silly Putty is what I call "pious imagination," our inventing something to explain a discrepancy and then treating the piece as though it had come that way directly out of Scripture. For instance, the Fourth Gospel says that Peter was from Bethsaida, and the Synoptics say he was from Capernaum. Pious imagination takes care of the gap (a matter of less than five miles) by explaining that Peter, at some point, moved from Bethsaida to Capernaum. Of course, there is no textual evidence for that solution, yet there is a sort of mind that just has to have the matter settled, whereas the scholarly mind prefers to let the facts stand as they are, to accept the incongruity of the Gospel's saying "Bethsaida" where the Synoptics say Capernaum." What difference does it make which is historically accurate? Peter (perhaps living halfway between) undoubtedly was familiar with both towns.

However, if we start from the premise that, in order for the Scriptures to be Scripture, it must be taken as certain that all the pieces from all four Gospels will indeed fit together into one factual puzzle picture of the history of Jesus--if we start from this premise, then it is probably inevitable that, in our efforts to force that picture, we will fall into "fudging." And this is precisely why the "scholars" therefore ask us to consider the possibility that we may be misunderstanding and misusing the Gospel evidences in even wanting to jigsaw-puzzle them in such a way.

What if it were the case that it had never even entered the heads of the Gospel writers to give detailed, historically factual accounts of the sort we think they should have given? We would do well to remember that the passion for this sort of journalistic factual accuracy is entirely an invention of modern Western thought--about which peoples of the ancient world knew nothing. What if the Gospel writers were careless about such matters precisely because they could have cared less about that sort of picture of Jesus, not seeing that it would be of any particular Christian value to anyone? What if they knew--knew better than we do--that their pieces didn't even pretend to be journalistic "factual knowledge bits"? What if they knew that what they actually were handling were rather "story units of tradition" which had been passed along by word of mouth and which the passers-along had freely molded and shaped to give us the most theologically true interpretation of who Jesus was and what he signifies as God's revelation to us? Could it be that we have created the problem for ourselves in trying to read the Gospels as one historical jigsaw puzzle when they were meant to present us with a set of pictures of an entirely different sort?

Most people probably have never made the sort of detailed comparison of the Gospels that reveals just how much discrepancy of detail there is between them. Accordingly, many are likely to be shocked by what our study will now show to be the case. Some will even feel quite threatened--perhaps evresenting my bringing the truth to light.

In response, let me first of all point out that I am not creating these discrepancies; I am only pointing out what is in the texts. And, of course, any student of Scripture will want to start with a totally honest acceptance of what the texts (all the texts) actuually say.

Second, I will take pains to develop my view that these discrepancies in no way have the effect of challenging or questioning "the inspiration of Scripture." Rather they afford us a very helpful means for discovering just how "the inspiration of Scripture" was understood by the Gospel writers themselves.

And third, we will find that it is precisely the discrepanctes between the Gospels that give us our best clues regarding the respective authors—who each was, how each thought, and what each wanted to accomplish with his particular Gospel.

To help in our addressing these last two points, I shall lift up just one such Gospel discrepancy as an illustration. Because we are due to give it very detailed attention later, I will not now reveal as much as the chapter-verse locations. Please don't take the time to figure them out and look them up. The pro-and-con argument will come later; read what I say here as a simple illustration of the point I want to make. I also will be making some observations that will get supported only later. So, for now, don't argue--just read.

I have in mind the account of Jesus’ original seashore calling of his Galilean fisherman disciples. Mark’s Gospel is the one that has the best chance of being primary source material of precise historical accuracy. For one thing, Mark's account was written as much as twenty years before that of either Luke or Matthew. For another, there is the distinct possibility that Mark's account could have come straight from the mouth of the fishermen Peter--who, of course, was himself one of the fishermen called. And for a third, the accounts of Luke and Matthew appear to have been derived straight from the Gospel of Mark, those later writers not even showing evidence of information other than what they got from Mark.

Mark explicitly names the four fishermen involved as being two sets of brothers: Peter and Andrew, James and John. Then Luke in turn comes to write his version of the event. He gives evidence that he is working directly from Mark's manuscript and thus knows good and well that Mark had named four. Nevertheless, he chooses to name only three fishermen. Luke's account does not name Andrew, shows no knowledge that Peter had a brother, and gives no hint that a fourth fisherman was even involved.

So what does Luke's freewheeling treatment tell us about his own literary methods and particularly about his opinion of the historical reliability of Mark's work? Is Luke suggesting that he finds Mark's account to be not simply outside the inspiration of the Holy Spirit but actually quite unreliable--needing rewording, revision, and actual correction at point after point? (Luke will use hardly as much as a sentence from Mark without revising it to some degree.)

No, such an attitude cannot be Luke's. The fact that he is eager to copy almost the whole of Mark's Gospel into his own is proof enough of the authority and respect he accords Mark. Regarding the "gospel truth" of its content, Luke certainly honors Mark's Gospel as an "inspired writing." And of course, in light of their subsequent places in the canon, it is clear that the church has always considered both Mark's and Luke's Gospels to be "inspired writings"--even if that necessarily shows one inspired writer being very free to change the wording, details, and even historical references in the inspired writing of the other. How can this be?

To me, the obvious answer is that "divine inspiration" was never understood as extending to matters of theologically inconsequential detail. Certainly Luke would be the first to deny that he was in any way challenging that Mark's Gospel was "the word of God." No, he accepts the authority of Mark on every matter of significance--even while feeling free to change details (whether it was three fishermen or four on the seashore). Luke exercises this freedom simply to make his own his particular understanding and interests, to make a point perhaps just a bit different from the one Mark had been wanting to make. To put it otherwise, Luke's practice suggests that he saw the Holy Spirit as indeed interested in guaranteeing that the truth of the gospel was never intended to be synonymous with "the preservation of the historical exactitude of every jot and tittle of every writer's account."

And I propose that, if both Luke and the Holy Spirit have shown themselves ready to sit loose regarding all these minor Gospel discrepancies, perhaps we don't have to get uptight about them, either. They certainly do not indicate the infallible God's absence during the Scripture-writing process; they indicate only the fallible human beings' presence.

Yet notice, now, the positive possibility provided by discrepancy of this sort. We have seen that Luke's decision to write "Andrew" out of the scene had to be deliberate rather than accidental. We can assume, therefore, that Luke must have some reason for what he did; it can hardly be that he was simply playing fast and loose with the details Mark provided. So, if we can figure out why Luke felt led to make the change, that just might tell us something quite important about Luke's understanding of things. And it now gives me great joy to announce that Luke has been figured out. All you have to do is keep reading (for some number of pages) and you too will know. (Sorry about that, but you are not yet in a position to receive the truth. We have miles to go before we sleep.)

The Method

We are still committed to learn as much as Scripture can tell us about the Beloved Disciple, author of the Fourth Gospel. Yet in order to do that we must first discover the import of the fact that the Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) focus on the Galilean Twelve whereas the Fourth Gospel focuses upon its Beloved Disciple.

Our method will be to do a great deal of comparing of the Gospels back and forth. Yet what we are after is not the customary "harmonizations" or what seems "the most historically plausible account." Most often in doing Gospel comparisons, we look for ways of explaining away apparent disagreements so that the different evangelists can be understood as actually telling a single story. Or we take their discrepant accounts and try to reconstruct the version that is the most historically plausible. Such an exercise is, of course, entirely proper and even necessary--yet this is not at all what we are undertaking now.

Our method will be what is technically known as "redaction criticism"--namely, the effort to read the mind of the final writer of each Gospel, to determine what he wanted to communicate in arranging his material and in wording it as he did. We are looking particularly for the "divergencies" between one Gospel and another. Once we find them, we will insist on letting them stand as divergencies—even where there might be perfectly obvious ways of harmonizing them. Thus we will regularly ask, "Why would this writer have wanted his account, in this detail or that, to be different from the others?" We will truly be "reading clues" in the manner of Sherlock Holmes.

We start from the premise that is now common to New Testament scholarship--namely, that the Gospel of Mark was the first to be written, and that, in writing their Gospels, Matthew and Luke each had a manuscript of Mark at hand and regularly copied from it. The Fourth Gospel, then, is a later work whose writer chose not to follow the common Markan "synopsis" that accounts for so much of the unity of the first three Gospels.

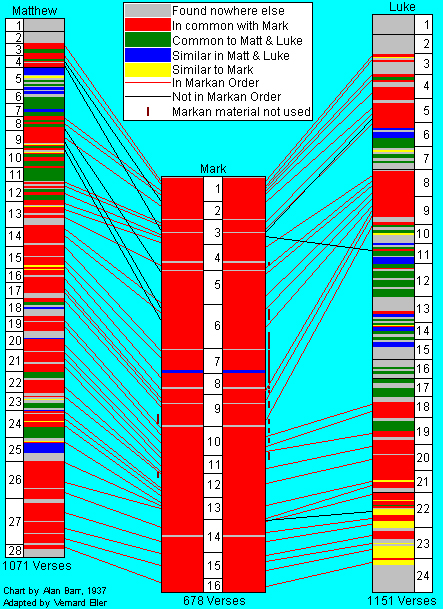

Explanation of the Chart

The chart here is a miniaturized version (done at great sacrifice of detail) of a large wall-hanging chart that made it possible to trace almost verse by verse the borrowing between the Gospels. Our specimen can present only in a general way the evidence that has led scholars to their conclusions regarding sources. Even so, it must be understood that the chart not committed to any particular theory of how they came to be related as they are. It simply shows where we find the material that is identical--or very similar--from one Gospel to another (what we shall hereafter call "borrowings"). The chart does nothing more than present the factual data which must, then be explained by this or that theory.

"Borrowing" would seem to be the only possible explanation for the close textual similarity of the material. If it were a case of the Holy Spirit's dictating the text to one Gospel writer and then to another, there obviously would be no variation or discrepancy at all. It would be inconceivable, for instance, that the Spirit would tell Mark to write that there were four fishermen called to be disciples and then tell Luke to write that there were only three (or that the Spirit would give Matthew a different version of the Lord's Prayer than he gave Luke). If, on the other hand, each Gospel writer had worked solely from his own memories, in complete independence of the others, then there is no way that the similarities among the Gospels could be as striking as they actually are.A few scholars want to argue that Matthew is the original Gospel and that Mark is a condensation of it and Luke a revised edition. Throughout our treatment, however, we will assume the much more common theory--namely, that Mark, the short Gospel, was written first, and that Matthew and Luke are separately expanded versions of Mark. Presumably, in addition to using copies of Mark, both of these writers also had at hand copies of a collection of the sayings of Jesus (now identified as "Q"), which each in his own way added to his Markan borrowings while at the same time working in his own special materials. According to this theory, then, the chart reads as follows:

The NUMBERED BLOCKS of each Gospel identify chapter divisions (thus indicating the length of the chapter, and finally of the book as a whole, on a scale of so many verses per inch). Thus we see that Luke has more verses even though Matthew has more chapters--and that Mark is but a bit more than half as long as either of the other two.

In whatever column it appears, GRAY represents unique material in one Gospel that is quite unlike anything in any other Gospel. For example, Mark has no "nativity stories" (and Q wouldn't even be expected to have had such). Accordingly, the "gray" of Matthew's first two chapters shows that his nativity account is uniquely his own. Likewise, the "gray" of Luke's first two chapters indicates not a commonality with the "gray" of Matthew but the very opposite: Luke's nativity story is also uniquely his own. What we have here are two quite different accounts showing that neither Matthew nor Luke was familiar with the other's information.

Likewise, the scattered bars of gray in the Mark column represent the very few verses not borrowed by either Matthew nor Luke. The small patches of brown that appear in a kind of dot-dash pattern close along on either side of the Mark column indicate that Matthew chose to reproduce almost the whole of Mark in his own Gospel--but that, for reasons of his own, Luke chose not to use considerable portions of Mark's chapters 6-9.

Wherever it appears, RED represents material that Matthew and/or Luke have in common with Mark--material that Matthew and/or Luke likely borrowed from Mark. Of closely related significance, the YELLOW resents material in Luke and/or Matthew similar to that in Mark, though not close enough to be called common. In most it probably represents Markan material that was revisedin the borrowing process. However, it could identify cases in which Matthew and/or Luke took from sources of their own a similar to (but not identical with) one from Mark and so passed over Mark's story I favor of their own particular version.

The GREEN represents material common to Matthew and Luke (though obviously not taken from Mark, since none of it appears there). We are as much as to conclude that Matthew and Luke must have possessed--in addition to their respective copies of Mark--copies of another common document from which each borrowed. When tracked down in the Gospels, the material indicated by the green invariably is found to consist of "teachings of Jesus." Consequently, there is nothing to suggest that the Q document ever was a "Gospel" in the sense of being a narrative account of Jesus' life. Q has been preserved only in these borrowings of Matthew and Luke, although there may be a reference to it in Eusebius's fourth-century statement: "Matthew compiled 'the sayings' in the Aramaic language and each person interpreted them as he was able."

- The BLUE is a variation of the green representing material in Matthew and Luke that is similar(though not close enough to be called common). For the most part, it is probably Q material that one or both of the writers revised enough to blur the obvious commonality.

Now, with both this chart and one of the Gospels before us, the procedure of the writer can become quite apparent. For instance, Matthew wants to begin his Gospel with narratives of Jesus' birth. Because neither Mark nor Q have anything to offer, his first two chapters must be drawn entirely from his own special sources. With chapters 3-4, then, he picks up on Mark's account, mixing in but little information from anywhere else. Chapters 5-7 are, of course, the Sermon on the Mount. Again, Mark (which is almost entirely narrative with comparatively little in the way of teaching material) is of no help, so Matthew constructs the Sermon by arranging and editing Q material. This material that Matthew presents as a three-chapter continuity is the same material that Luke scatters throughout the entire middle part of his Gospel. Finally, for his Passion account of chapters 26-27, Matthew copies directly from Mark--and then Closes the whole with his own unique "gray" account of Jesus' post-resurrection "last Words."

The Fourth Gospel does not appear on our Chart because there is nothing to qualify it for such appearance. Although it of course has a number of the same stories of Jesus that the Synoptic do, there is no evidence indicative of "borrowing, " of common sources, of familiarity with anyone else's work, or of direct interconnections of any sort. The Fourth Gospel is truly an independent creation.

|

Copyright (c) 1987 |